Dominic Papillon

Galerie Bellemare Lambert April 8- May 6

À l’ombre d’une corolle

The title of Dominic Papillon’s latest solo exhibition at Galerie Bellemare Lambert loosely translates to In the Shadow of a Flower Blossom. Both the show’s title and the titles of the works provide poetic entry points, giving us a riddle or a clue while not telling us everything. I first noticed Dominic Papillon’s work at Papier in 2022 when his sculpture, Dure-Mère II was presented at Galerie Bellemare Lambert’s booth. At the Belgo, I was able to enjoy this paper, wax, and watercolour figurative sculpture more slowly. Dure-Mère II directly translates as “hard mother”, but the phrase is a scientific term for the outermost membrane of connective tissue which protects the nervous system, the dura mater. This is an interesting play on words, evoking both the ubiquitous human experience of being born to a mother, and also a thin layer that protects our vulnerability. This hollow sculpture represents a walking or posing human form, the sex unidentifiable. The paper and wax construction seems to refer to the delicacy of the human body, while the vibrant hues of the watercolour bring it to life. A headless and hollow form, this sculpture is in its foundation paper white flecked with salmon pinks and blues which give it the appearance of a gorgeous seashell, but also of disease, or varicose veins visible through translucent human skin. This seems to be a skin that someone has shed, leaving a shell behind.

The work of Papillon is often simultaneously beautiful and grotesque. It calls to mind the complexity of the human condition, in that all that is gorgeous, enjoyable, and pleasurable in life is also temporal and bound to fade or end abruptly. We exist in places and forms which can have only temporary beauty; the material world is continuously replicating itself and leaving behind what is outworn. Is the frailty of the human condition what makes life so precious? When will the threat to the survival of our species make us treasure our own lives and the life of our planet?

Born in Quebec, Dominic Papillion lives and works in Montreal. He obtained his baccalaureate from UQAM in visual and media arts, and his master’s degree in sculpture from Concordia, where he now teaches sculpture. He is represented by Galerie Bellemare Lambert and he has shown there since 2015, and has had other solo exhibitions at Maison de la culture Frontenac, Plein Sud in Longueuil, Circa Art Actuel in the Montreal, Regart in Lévis, Sporobole in Sherbrooke, and Galerie Verticale in Longueuil among others. Papillon’s use of the human form in a playful but also serious way to evoke emotion and the human experience reminds me of the character of some works by Kiki Smith and David Aljmedt, but, of course, he has his own unique language.

Perhaps the most striking piece in the exhibition is a wall-mounted human form at the back of the first room in the gallery. Humeur acéphale II shows a limp, headless body with a sickly pallor, stuck to the wall with large daubs of pink or wine-coloured wax which resemble deflated balloons or oversized flower petals. These coloured wax pieces stand in warm contrast to the corpse-like tones of the figure, which, laying limp, recall Jesus being taken down from the cross, a scene recreated by so many artists during the Renaissance as The Deposition. Gallery director Christian Lambert said he admired the figurative wax pieces for their resemblance to marble, and indeed Papillon’s wax works do evoke classical marble figures from antiquity.

The grotesque has long been a part of Christian art, with sculptures of suffering Christs or saints martyred prominently displayed, mostly in churches, reminding us of their stories. A wax figure also evokes death in other ways, sometimes creating a look that is reminiscent of the tradition of human bodies presented after death preserved in formaldehyde, made up and patched up with putty so that their loved ones can regard them one last time and say goodbye. Our culture has a strange relationship with life, often not valuing it while alive, but also not giving much attention to death, avoiding thought of such matters, thereby keeping death out of sight and out of mind. Wax is an interesting medium for a sculptor to work in, it resembles the human body in texture and feel, and as such, it can be used to get remarkably life-like effects. The heating and drying process of the material makes it very malleable, but also vulnerable to changes in temperature. Wax is also used by sculptors in techniques such as with lost wax casting. Wax work figures are a fascinating and kitschy human preoccupation often shown in museums as a tourist attraction, showcasing famous figures in a bizarre state that is at the same time very life like, very dead, and also often comical.

One of the most intriguing pieces in the show is Papillon’s Humeurs acéphales, a ceramic work where the figure is cast in nearly matte black is emerging from underneath a gold-coloured blanket made from thick coils. The person underneath seems to be undergoing some sort of transformation, and three feet can be seen along with three hands. Is there more than one being underneath, engaging in carnal activities? Or do the hands and toes tense from pain? No head can be seen, and from the title we can wager that what is felt is of the mind, not of the body—the title of the piece translates as “headless mood”. To quote Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, “don’t lose your head!”

Alanguissement is another work that plays on words as well as forms, and brings some levity and pop-style (think Rocky Horror or the Rolling Stones). The word alanguissement means languor, which is a mood of lassitude or indolence. A langue is a physical tongue as well as a language, and a huge, lolling, red wax tongue is what replaces the face on this pallid waxen bust. The man seems to be taste itself, his shoulderless huge throat emphasized by the way it emerges from the wall. Most of the head isn’t present, it is simply a massive, smooth, wax tongue. What if taste had a face? What if, in the sensual experience of being in a body, taste consumed you were little more than a tongue? What kind of languor could bring about such a moment? Can our desire ever be sated?

On the wall and floor we find Abattis I, II, III. Generally speaking, they are iron-coloured ceramic works representing roughly-hewn body parts. Abattis I is a skinny arm, Abattis II is an arm, elbow and forearm, and Abattis III is a more abstract and barely identifiable torso which is presented on the ground. An abattis is a weapon formed from a branch of a tree, sharpened, and laid out defensively before the enemy in war to delay their approach, so that they may be fired upon to exact the maximum damage. Are these body parts the weapons or parts of the bodies that were wounded by the weapons? Or both, as a human race we destroy each other, despite being one family. These body parts look worn down and manipulated by touch, we can see the impressions of the artist’s hands and fingers. The effect is reminiscent of the consequences of being human. It makes me think of all that touches us, damages us, wounds us, all the ways we cause hurt and are hurt in turn.

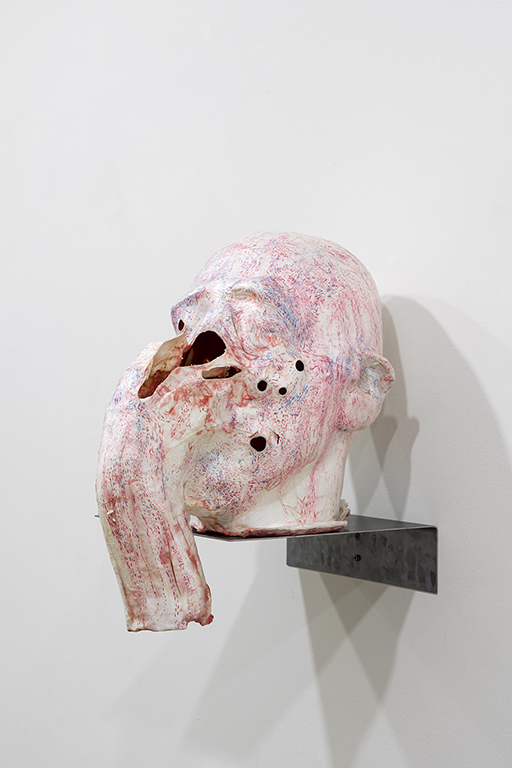

Near the Abattis sculptures is Dure-Mère I, a paper bust where the head seems to be tearing away layers of its own face with its hand. Like its sister piece, Dure-Mère II, this sculpture is also made from paper, wax, and watercolour, and the colour palette is the same. We seem to be able to see through its transparent skin to the capillary and vein systems. The piece is both lovely and discomfiting. Papillon’s work is unsettling in the way it reminds us of our own mortality and vulnerability, he seems to play with the human body in sculpture like a scientist dissecting a cadaver. In fact, Papillon’s work in this series reminds me strongly of surgical models used to train medical students, disturbingly lifelike, but also clearly not alive. These sculptures are momento moris, reminding us of our ultimate demise, but also of the beauty inherent in the forms which allow us to exist on this earth, to feel, to experience, and to create.